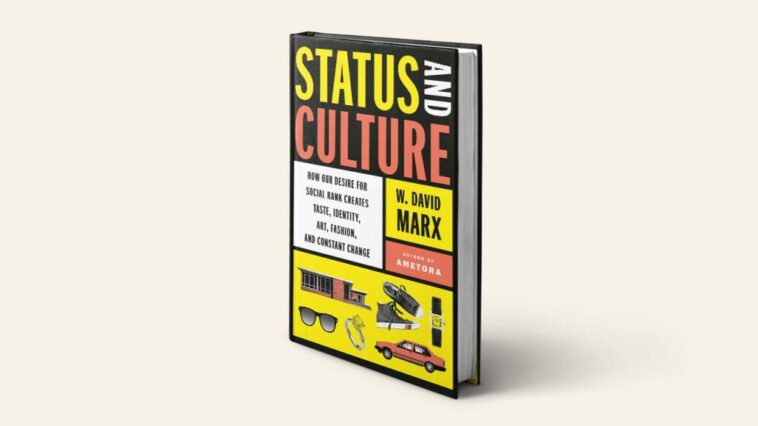

En Estado y cultura — el nuevo y atractivo libro de no ficción que parece estar en la mesa de noche de muchos ejecutivos creativos — el autor W. David Marx analiza varios miles de años de cultura popular en busca de una convincente teoría unificadora del “por qué”. ¿Por qué ciertas cosas despegan (una canción pop, un corte de jeans, un género cinematográfico) y luego pasan de moda, solo para volver misteriosamente a estar de moda años después? Marx dice que el ingrediente mágico es el estatus, esa escurridiza moneda social sobre la que se construyó Hollywood.

Gran parte de la cobertura mediática del libro se ha unido en torno a la idea de “estasis cultural”, o que la cultura actual, en todas sus formas y a pesar de (o quizás debido a) la instantaneidad de Internet, está en una depresión. Pero eso no es exactamente lo que Marx está diciendo, como explicó en una animada discusión de Zoom con El reportero de Hollywood desde su casa en Tokio que toca todo, desde venderse hasta películas de superhéroes.

Su libro está recibiendo mucha atención por tratar de hacer algo nuevo: asignar un análisis cuantitativo a la cultura.

Durante mucho tiempo estuve frustrado porque no había una explicación particularmente buena de por qué la cultura cambia con el tiempo. Hay todos estos comportamientos predecibles en términos de moda y, sin embargo, estaba muy intrigado por el misterio de por qué suceden exactamente estas cosas. Y si estudias economía o todos estos otros campos, tienes explicaciones bastante claras para el comportamiento humano. Y sentí que con la cultura todo era muy abstracto y muy inespecífico.

Me embarqué tratando de juntar todas estas cosas, todas estas diferentes teorías y todo lo que había aprendido a lo largo de los años. Y al hacerlo, descubrí la parte del estado como el hilo unificador que le daba sentido a todo. Fui a la biblioteca tratando de encontrar el único libro sobre el estatus. Y descubrí que no había realmente un texto autorizado sobre cómo funciona el estado. Entonces, a partir de ahí, me di cuenta de que podía hacer un libro que explicara cómo funciona el estatus y cómo funciona la cultura y cómo funcionan juntos.

El estado puede ser muchas cosas diferentes. Entonces, ¿cuál es su definición de estado?

El estatus es su posición en una jerarquía. Y estamos en todas estas diferentes jerarquías en nuestras vidas. Una comunidad local, su escuela, su lugar de trabajo, su familia: puede tener un lugar en la jerarquía. Si asciendes en la jerarquía, obtienes más beneficios, la gente te trata mejor y tienes una vida mejor. Y si te mudas hacia abajo, tienes una vida peor. Los psicólogos sociales han realizado muchos experimentos y estudios en los que descubrieron que el bienestar de las personas aumenta absolutamente cuanto más tienen una posición relativa sobre sus compañeros y disminuye si tienen una posición más baja.

Pero lo importante de lo que estoy hablando en el libro no es simplemente que la gente exija constantemente ascender, porque eso no es necesariamente cierto. Es simplemente que incluso normal, lo que yo llamo estado normal, que es simplemente estar en un grupo y ser un miembro de buena reputación, tiene beneficios y se siente bien ser parte de una comunidad y la gente se preocupa por eso. Y simplemente preocuparse por lo que otras personas piensan de ellos y los beneficios que obtienen de eso es realmente lo más importante que entiendes para la creación y formación de la cultura.

Una vez que comprende estos principios de búsqueda de estatus, comienza a comprender por qué estos comportamientos arbitrarios, porque la cultura es, en última instancia, un conjunto de formas arbitrarias de realizar ciertas actividades, por qué nos enfocamos tanto en ciertas en ciertos momentos y luego cambia con el tiempo.

Siempre supuse que la cultura tiene ciertos líderes de pensamiento que le muestran al mundo algo diferente que no sabían que querían, que llega exactamente en el momento adecuado y luego, de repente, todos los siguen. Como Andy Warhol, David Bowie, a la gente le gusta eso. Entonces, ¿cómo encaja eso en su tesis?

Hablo sobre el papel del estatus en la inspiración de artistas en el libro. No digo que todos los artistas quieran estatus social y por lo tanto creen. A lo que me refiero principalmente es dentro de la comunidad artística, especialmente para, digamos, algo así como el arte de vanguardia: si creas formas innovadoras de cultura y no eres reconocido como artista, es posible que esas ideas no sean reconocidas como arte. Entonces, es muy importante que los artistas obtengan lo que yo llamo «estatus de artista», que es que, si se los ve como artistas, el trabajo que hacen [is deemed[ art and then people can have aesthetic experiences with that.

I would say David Bowie was someone who was pretty singularly obsessed with becoming a star and finally achieved it. Warhol was a commercial artist who desperately wanted to be a fine artist and in his case he decided to paint two different styles of art: abstract expressionism and then what became pop art. And he showed them around the different galleries and got feedback and then went into the pop art direction. And ended up, because he was in that cycle of artists, knowing what the future direction could be for art.

One of the things I’m trying to say about where new art comes from is it always comes from a very specific social context. Even if these people feel like geniuses, they’re reacting against what came before and the next wave of people will also react against what they did. But what motivates them, in a sense, is to create status for themselves as artists by negating the previous styles and creating space for themselves.

And also it sounds like having an innate sense of what is commercially viable or appealing to a mass audience.

I think that’s become increasingly important. But obviously someone like Marcel Duchamp, who was absolutely one of the most important artists of 20th century, did not care about commercialism at all. But he understood, I think, what would be the most radical negations of Picasso and Batiste and the art at the time that would get attention and devalue the art that came before. I think in the late 20th century we’re getting to a point where people have to be very commercially savvy, but it’s just knowing what is going to obviously get you attention as the next step in the narrative of the history of art and culture.

What about this notion that “selling out” doesn’t really exist anymore? That used to be a real big deal and now some people think that commercialism has become so prevalent that it doesn’t even exist as an artistic philosophy.

“Poptimism” was a critical movement in the early 2000s that more or less said, “Why are we so focused on innovation in indie rock when rock is a pretty stale form and most of the really cool production and interesting ideas are happening in R&B, hip hop and those fields?” That initial poptimism, which was a really, I think, an egalitarian look at, “let’s try to weigh all culture in the same way and give it attention, even if it’s popular, if it’s indie,” I think that has now moved to a sense that things that are gigantic blockbusters need our attention more than things that are underground because they matter to more people and that’s where our attention should be. So it’s kind of a somewhat of an ultra democratic impulse, but it also is, I think, crowding out some of the time and attention that used to go to indie culture.

You’ve mentioned the “b” word — blockbuster — so let’s move into movies. What’s your assessment of where Hollywood is right now when it comes to movies?

All creative industries are faced with a major problem, which is that you can’t predict demand for your specific products. It is nearly impossible to predict what will be a hit and what won’t. And what you do is you try to use a bunch of techniques in order to better predict demand and to create products that are much more reliable, in terms of success in the commercial market.

I think the question for today is not why are big studios making sequels and really ultra-safe movies, because that is the economic imperative that they have. I think it’s instead: Why is there no pressure from auteurs or indie creators — who in some ways devalue what’s going on in the mass market — so that the big studios have to respond. Something has changed with the internet and with our economy right now, that either those indie creators are co-opted, or that their message, or the assault that they have on mass-market tastes, has been blunted.

So is that all to say that we’re in a moment of stagnation or a less creative moment?

That’s certainly what people are feeling. And I think there are some measures of this. The reason people bring up that there’s so many sequels, there’s been so many Spider-Man films, is because that does seem like a sign of stagnation. And if you grew up in the 1990s, which people who were over 40 did, they just remember Pulp Fiction and they remember Clerks and they remember Good Will Hunting.

I think some of this is a little bit glossy nostalgia in the sense that there was no internet video when we were kids and our lives were transformed by these things and we wished to be inspired by these kind of films. Again, young people, people under 25, maybe so transfixed with what’s on TikTok all the time that maybe they don’t necessarily worry about the stagnation issue.

But by the measure of 20th century, in terms of what are the big films and who are the musicians, then the amount of change that we’re seeing, the amount of tweaks to the conventions of the art forms, seems to be moving in a slower pace. I don’t think that stagnation necessarily means that people are all bored or that everybody is upset about it. But if you are a cultural critic and your entire way of thinking about the health of the culture is the pace at which conventions of these fields change, and they feel like they’re moving forward in new interesting directions, people have tended to be disappointed in the last 20 years.

But then if you look at TV, there’s just this glut of streaming content that is very creative and out of the box.

I do think that’s where people’s attention has gone. But I think there’s also become a formula for this kind of TV creation. There’s a cadence to the way these streaming TV shows are made and the way that the cliffhangers are given at the end, so you keep clicking, I think we’re growing a little bit tired of. So I think the health of that ecosystem in the last five years can’t predict necessarily what the next five years will be.

My whole contribution in the book to this debate of “cultural statis,” is not necessarily that there’s not good things being made. It’s just that when you have so much of it and it moves so quickly, we don’t necessarily form the bonds to it and it does not become representative of people’s identities the same way that culture used to in the past. If you’re just in a world of infinite content, it is really depleting the social meaning of the things that we consume.

At the same time, I feel like there is a lot of great culture happening right now. The films coming out of the festivals this year look very exciting to me and nothing I’ve seen before. And then people do rally around certain TV shows, like the fourth season of Stranger Things. And it really dominated all summer and then revived Kate Bush’s career in a way, or made her bigger than she ever was. The Squid Game phenomenon, these phenomena still occur.

Absolutely. Culture still exists. Culture is still an ecosystem that moves — but I think the fear is that it’s just not moving as much. Is there new culture that’s entertaining people? Absolutely. Is there really interesting stuff still going on? Yes. The Rehearsal was an incredible TV show unlike anything I’ve ever seen before. And people talked about it in that sense. And so this is not at all to say that nothing’s interesting anymore. It’s simply, at a macro scale, people feel like they’re not getting the kind of innovation that will make them inspired anymore — but this may have to do with our perception as much as it has to do with the actual reality on the ground.

I think a big part of it is that people are getting annoyed with just the number of comic book movies the studios produce.

Which is funny, because you just don’t have to watch them.

Right.

I have the Criterion channel. I have not watched all the films on the Criterion Channel. If I’m really bored with the Marvel movies, I can just watch those instead. But the entire dialogue gets sucked into these blockbusters. And so we feel like we have to have an opinion on them and that people may be resentful of that.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.